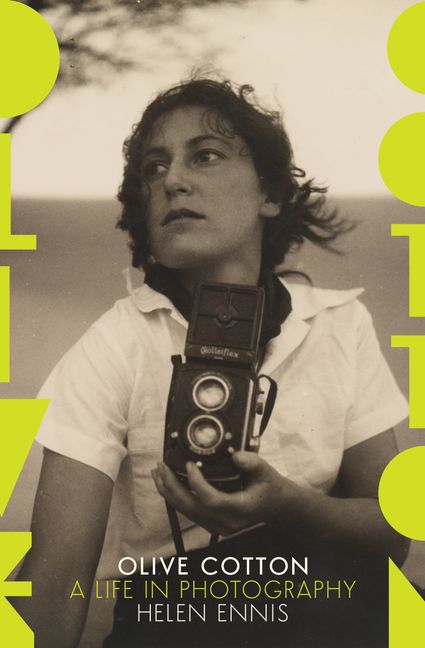

Olive Cotton: A life in photography

Helen Ennis, 2019

About

A landmark biography of a singular and important Australian photographer, Olive Cotton, by an award-winning writer – beautifully written and deeply moving.

Olive Cotton was one of Australia’s pioneering modernist photographers, a woman whose talent was recognised as equal to her first husband’s, Max Dupain, and a significant artist in her own right. Together, Olive and Max could have been Australia’s answer to Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, or Ray and Charles Eames. The photographic work they produced during the 1930s and ’40s was extraordinary and distinctively their own.

But in the early 1940s Cotton quit their marriage and Sydney studio to live with second husband Ross McInerney and raise their two children in a tent on a farm near Cowra – later moving to a hut that had no running water, electricity or telephone. Despite these barriers, and not having access to a darkroom, Olive continued her photography but away from the public eye. Then a landmark exhibition in Sydney in 1985 shot her back to fame, followed by a major retrospective at the AGNSW in 2000. Australian photography would never be same.

This is a moving and powerful story about talent, creativity and women, and about what it means for an artist to manage the competing demands of art, work, marriage, children and family.

Helen’s research on Cotton has been supported by the Australia Council Literature Board and the ABR George Hicks Foundation Fellowship; and related essays have been published in Meanjin and ABR.

Released 21 October 2019.

544 pages ISBN: 9781460758342 Published by Fourth Estate, an imprint of Harper Collins

Reviews

Martin Edmond, Australia and New Zealand Journal of Art, issue 2, 2020, pp.293-296

‘an exquisite tribute … [This] book is historically acute, wide-ranging in its concerns, comprehensive in its understanding of the times, meticulous in the reconstruction of people and places – and leaves enough unsaid for us to be able to feel both the enigma of Olive cotton’s life and the wonder of the work she made.’ ‘[Ennis] shares the modesty and restraint of her subject in such a way that you come to understand that it is the unknown in a life that are most precious: the ephemeral, the evanescent, the undeclared.’

Susan Wyndham, ‘The artist in black and white’, Look, January/February 2020, pp.55-56

A ‘superb biography … Ennis draws on decades of knowledge and meticulous new research to create a finely nuanced portrait. … Ennis makes a detailed, perceptive analysis of Cotton’s work (with generous illustration) … Ennis’ clear-eyed appreciation of [Cotton’s] photographs sets Cotton firmly in Australian art history and this beautifully designed book celebrates both artist and author.’

Helen Elliott, ‘Why Olive Cotton turned her back on photography’, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 January 2020

Alison Stieven-Taylor, ‘Olive Cotton: A life in photography’, ABR, January/February 2020, no.418

Ennis has ‘managed to weave a compelling, if at times diaphanous, narrative… a fascinating historical account that is captivating and illuminating.’

Patricia Anderson, ‘Life’s work in a trunk of treasure’, The Australian, December 21-22, 2019

‘Author Helen Ennis has penned a richly detailed biography … Ennis’s forensic imperative has painted a thoroughly illuminating picture of her subject.’

Richard Johnstone, Irresistible attraction, Inside Story, October 2019

An ‘absorbing biography … As biographer, Ennis must deal not only with the elusiveness of Cotton herself but also with the larger-than-life personalities of the men she married. It is a balancing act to give these two talkative and often charming men their place in the story while keeping Cotton very much in the frame, ever alert to the danger that she will slip into the background. One of the fundamental strengths of Ennis as biographer is that she achieves this difficult balance, giving both men their due and never rushing to simple judgement, while at the same time ensuring that the main light falls consistently on her central subject. As she reminds both herself and the reader at one point, “this is Olive’s story.”’

Awards

- 2022 Adelaide Festival Awards for Literature Non-Fiction Award

- 2020 Canberra Critics’ Circle Biography Award.

- 2020 Magarey Medal for Biography, Australian Historical Association.

- 2020 University of Queensland Non-Fiction Book Award, Queensland Literary Awards, State Library of Queensland. Watch the acceptance speech here.

- Longlisted for the 2020 Mark & Evette Moran Nib Literary Award

Resources

- Helen’s reflections on the Olive Cotton project

- Extract from Good Weekend

- Interview on The Art Show, with Ed Ayres, ABC RN [audio available]

- ‘Irresistible attraction’, review by Richard Johnstone, 24 October 2019. Republished in The Canberra Times, 9 November 2019

- Extract, Art Guide Australia, 31 October 2019

- Extract, Inside Imaging, 3 December 2019

- Podcast and transcript from National Library of Australia launch. In conversation with Alex Sloan. 28 November 2019

Available from

On writing the biography

I wrote this book because I have always loved Olive Cotton’s photographs. I wanted to better understand them, the reasons why they look the way they do, and what they’ve contributed to Australian art and culture. But I also wanted to delve into Olive’s life, the life of a particularly creative woman, which is why I chose biography rather than any other kind of writing. In my view, a successful biography makes illuminating connections with our own lives and times and I feel sure that Olive’s complex life story has the potential to do that. Some of the themes the book explores concern marriage, motherhood, creativity, ageing and mortality. While the biography deals with the specific details of Olive’s life, the larger context is of course Australian society and culture in the twentieth century (Olive was born in 1911 and died in 2003).

The chapters in the book discuss Olive’s life, her work and individual photographs and include reflections on the biographical process. I have aimed to achieve the momentum of a novel in which the narrative is inexorably propelled forward.

There were three main challenges in writing the biography. Olive’s retiring disposition and her circumstances meant she placed very little on the public record about her views on photography, or about her private life. Secondly, very few personal items that give an insight into her beliefs, motivations and feelings have survived. Lastly, she was married to two charismatic, domineering men – photographer Max Dupain and farmer Ross McInerney – who kept rearing up in the narrative, threatening to overwhelm it. My struggle was to give substance to a sometimes shadowy, enigmatic figure and to ensure that her voice could be heard. Focusing on Olive’s photographs was intrinsic to that process. So was paying attention to the little, often complicated details of her life, a woman’s life. And finally, whenever I could, I quoted Olive directly, from letters, conversations, and a handful of formal interviews conducted when she was aged in her seventies and eighties.

Olive Cotton revelled in the expressive possibilities of photography and, despite the sometimes extreme difficulties she faced, she always believed in the value of a creative life and the importance of art. The photographs she created are her legacy – I am grateful for them and hope this biography will help them find an expanded, appreciative audience.

Helen Ennis